BLACK FLAG

Santiago Sierra

"I wanted to create an anarchist icon that was a source of pride and courage; that made you think that the planet is ours when you saw it." SANTIAGO SIERRA

NORTH POLE

SOUTH POLE

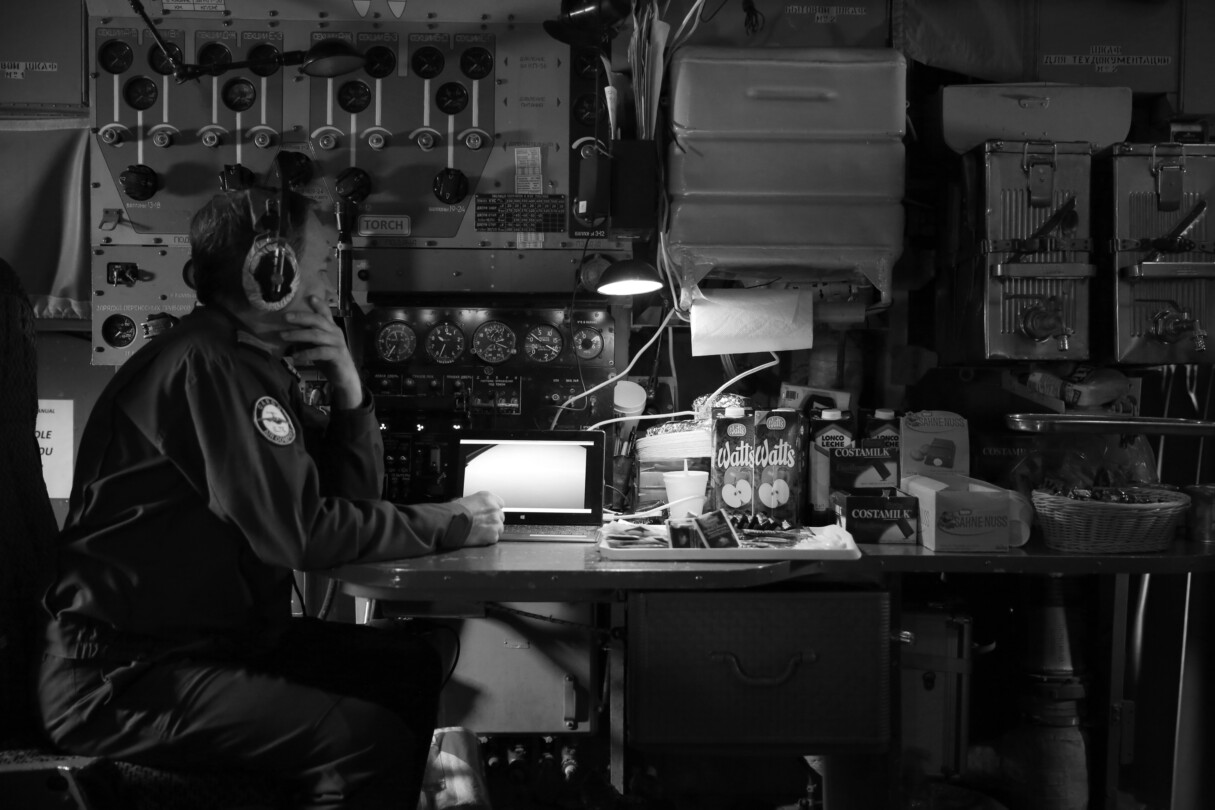

documentary images (NORTH)

documentary images (SOUTH)

Essay

Occupy the World!

By Uri Gordon

As we pass the centenary of the First World War and the bicentenary of the European Reaction, nationalism once again proves the ultimate foil to the promise of social movements from below. The torch of the alter-global mobilisations of the millennium may have been successfully carried on to Zucotti Park, Taksim Square and Puerta del Sol, but now we are in the midst of the inevitable backlash – this time without as much of a 9/11 to excuse it. Neoliberalism’s shattered promises of prosperity and stability have given way to bare-faced chauvinism, as threatened privilege turns against the old and new victims of its scramble for resources. Yet the current rise of nationalism extends beyond the revanchist reflexes of threatened elites. As the devastating consequences of unfettered corporate power came home to roost in advanced capitalist countries, social movements too have retreated from globalised articulation and into their own national contexts, often abandoning revolutionary anti-capitalism in favour of a horizontalist reformism heavily implicated in electoral politics.

It is in this double context that Santiago Sierra’s Black Flag assumes such an urgent significance. As a demonstrative attack against the nation and the state, this action pierces the global acupuncture points of arbitrary geographical designation (longitude, time zones) and symbolic territorial claims (borders, flags). The work stands in confronting not only the drift towards authoritarianism and xenophobia but also the left-patriotism and liberal internationalism presented as their alternatives. It announces an anarchist vision of a world without borders, a landscape no longer inscribed with the designs of violent institutions, a stateless classless society. In the spirit of direct action and expropriation, it declares: “Occupy the world!”

The black flag has accompanied anarchist, anti-state and anti-capitalist struggles for over 130 years. It is, most immediately, an anti-flag – presenting a direct threat and challenge to the authority and interests of states. Yet for anarchists the black flag has a much deeper significance – a symbol of the misery, hunger and death against which they struggle, and of the negation aimed towards their root causes. Louise Michel, a hero of the 1871 Paris Commune, was first to propose it, a decade after its bloody suppression, as symbol of mourning for fallen comrades, 20,000 of whom had died at the hands of the state. She flew the black flag in Paris on 9 March 1883, at the head of a demonstration of hundreds of unemployed workers. Shouting “Bread, work, or lead!” they raided three bakeries before being arrested. Michel received six years in prison. The black flag would make its first American appearance at an anarchist demonstration in Chicago the following year. It soon became an internationally recognised symbol of the movement.

Until the 1917 revolution in Russia, anarchists worldwide flew black as well as red flags. Yet this ended with the Bolshevik state suppression of the left and anarchist opposition. Nestor Makhno’s anarchist partisan army, which for over two years successfully fought off both the Red and White Armies to keep a large portion of the Ukraine under stateless communism, flew black flags embroidered with the slogans “Liberty or death” and “The land to the peasants, the factories to the workers”. During the Spanish Civil War, which saw an anarchist revolution in much of eastern Iberia, the diagonal red and black flag (and bandana) was popularised by the anarchist and anarcho-syndicalist fighters of the Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI) and National Confederation of Labour (CNT).

The anarchist movement, much of it physically eliminated by the end of the Second World War, began to regroup in the following decades, with many of the movements of the 60s and 70s rediscovering anarchist values and practices. Reintroduced in 1968 by protesting students in France and the US, the black and black/red flag has remained a prominent anarchist symbol around the world. In more recent times, black has been combined diagonally with other colours such as green, pink or purple to signify ecological, queer or feminist agendas within anarchism respectively.

Howard Ehrlich’s eloquent reflection on ideological and emotional symbolism of the black flag is worth quoting in full:

Why is our flag black? Black is a shade of negation. The black flag is the negation of all flags. It is a negation of nationhood which puts the human race against itself and denies the unity of all humankind. Black is a mood of anger and outrage at all the hideous crimes against humanity perpetrated in the name of allegiance to one state or another. It is anger and outrage at the insult to human intelligence implied in the pretenses, hypocrisies, and cheap chicaneries of governments.

Black is also a color of mourning; the black flag which cancels out the nation also mourns its victims the countless millions murdered in wars, external and internal, to the greater glory and stability of some bloody state. It mourns for those whose labor is robbed (taxed) to pay for the slaughter and oppression of other human beings. It mourns not only the death of the body but the crippling of the spirit under authoritarian and hierarchic systems; it mourns the millions of brain cells blacked out with never a chance to light up the world. It is a color of inconsolable grief.

But black is also beautiful. It is a color of determination, of resolve, of strength, a color by which all others are clarified and defined. Black is the mysterious surrounding of germination, of fertility, the breeding ground of new life which always evolves, renews, refreshes, and reproduces itself in darkness. The seed hidden in the earth, the strange journey of the sperm, the secret growth of the embryo in the womb all these the blackness surrounds and protects.

So black is negation, is anger, is outrage, is mourning, is beauty, is hope, is the fostering and sheltering of new forms of human life and relationship on and with this earth. The black flag means all these things. We are proud to carry it, sorry we have to, and look forward to the day when such a symbol will no longer be necessary.

(Ehrlich 1979)

As with much of Santiago Sierra’s work, in Black Flag what is displayed to the audience is not the artwork itself, but a documentation of its enactment (in this case two actions, one at each pole). While conceived for an art space, it is an explicit attempt to stimulate the audience’s imagination of how the action could have taken place in reality, to assert that that action did indeed take place and was not staged. The photography is not retouched or digitally edited, nor is it approached as a medium of artistic expression in its own right. A field recording, pressed on the displayed discs, is played back in the exhibition space – silent moments recorded at a high peaking volume, a silence which is not silence. Together with the replica black flag, the visual, aural and material account of the expressive action make it more immersive and immediate. The exhibition is perhaps best thought of as a souvenir – Sierra refers to it as a “relic” – of the actions themselves.

Again similarly to many of Sierra’s works, this piece involves a minimal gesture – a black flag planted in a white environment. The images created are reduced to their simplest, barest form – which would deliver an aesthetic experience even if emptied of all political signifiers. However, once its social and political resonances are amplified, it directs us towards a richer array of signification. Sierra’s stated intention was “to create an anarchist icon that was a source of pride and courage. That made you think that the planet is ours when you saw it.” I would like to argue that Black Flag fulfills this intention by subverting a perennial gesture of territorialisation.

Planting a flag is the most common ritual performed at the (much more frequently visited) South Pole. Lutz Henke, the producer who carried out the expeditions on behalf of Sierra, recalls it as a landscape crowded with flags. Most common are the smaller marker flags in different colours used to indicate function, boundary, route or potential danger around the Amundsen station. But most prominent are national flags: the flags of the Antarctic treaty states standing in a circle by the Amundsen station, the American flag usually found at the geographic south pole, and a host of smaller flags brought by every scientist and visitor. They carry flags from home, flags made by school groups, flags sponsored by charities, all left in the ice after the obligatory handstand and photo. Yet in all their good-naturedness, these rituals work to reify the artificial constructs of state and nation with the same power and affect as when a direct agent of the state carries out the action.

In his introduction to this publication, Philip Howe points out that the history of expedition has been central not only to polar exploration but also to conquest and colonialism – a history bound in a “nationalistic, soft-power matrix of symbolic visitation that culminates in the physical, penetrative act of planting the flag.” While it is ultimately through lethal violence that landscape is transformed into territory, the process of territorialisation also involves symbolic practices such as flag display and the renaming of places, as well as epistemic practices such as mapping, natural history and ethnography – all of which inscribe the occupier’s vision onto social reality.

At the poles, these practices are exposed at their barest. The uninhabited, poignantly ex-territorial landscapes of the Arctic and Antarctic accentuate how entirely fictional and facile territoriality is. A layer of political meaning imagined and transposed onto the landscape. Appearing as if they were colonial frontiers but perhaps even closer to the image of a sliced cake, the poles and their surroundings are mapped with state borders radiating inwards – yet the reality is one of neither natural nor artificial boundaries, only lines conjured and imposed across oceans and sheets of ice. In subverting the flag-planting ritual, Black Flag can be interpreted to implicate not only overt nationalism, but the entire epistemic apparatus of territoriality as directed by the colonial gaze – the mechanism by which north, south, east and west is determined and ingrained with obfuscated yet meaningful bias. Black flag, in playfully laying a claim from the poles to the entire planet, is also solemnly profound in its negation of the territorial terms on which such a claim would be made.

A more subtle line of attack is also present here, since the poles allow territorial gestures to often assume the innocuous guise of scientific and touristic internationalism, which Howe rightly characterises as “subverted forms of nationalism, thinly veiled in the licit authenticity of research projects and environmental preservation.” At the poles, the normalisation of the hierarchical organisation of human society is all the more insidious, as it hides behind the facade of peaceful international cooperation and the cosmopolitanism of elites, whereas just beneath this veneer we find the pettiness of nation states struggling over access, ownership and presence. Black Flag represents something different – it is not an attempt to reconcile different states’ claims to sovereignty, and by implication their claims to exterior territories through their sovereign power, but a challenge to very notion of sovereignty altogether. Encountering this work, audiences may begin to question how positive the image of different national flags standing together actually is.

Santiago Sierra is known for appropriating the actual social and political mechanisms that his work seeks to critique. Is this sort of tension or ambiguity not also found in Black Flag? Aesthetically speaking I am not sure this is the case. Sierra has drawn attention to the difference between his “many works of a hurtful ugliness” and this one, which he sees as his “most poetic” and “without doubt the most beautiful.” While the flag-planting ritual is appropriated, the use of a black flag inverts its significance in a way absent from his works that wallow in social problems. From an ethical anarchist perspective, however, the production of the artistic act does here place itself within some inevitable tensions.

For anarchists, the project to change society is bound up with a commitment to prefigurative politics – to being the change one wants to see in the world, actively building within the shell of the extant society a new one based on non-domination, voluntary association and mutual aid and practising these values in daily life. Not only are communes, collectives and cooperatives set up in this spirit – it also animates protests, direct actions and confrontational tactics. Hence, subversive and critical as Black Flag may be, its sheer cost is sure to raise eyebrows among activists. Indeed, the poles have become classed – and travelling there makes one part of a luxury tourist industry for the super-rich. With Arctic sea ice hitting record lows and the West Antarctic ice sheet verging on instability, the work’s high carbon footprint also becomes a perturbing issue. This is perhaps where we find the tensions present in other works by Sierra: his sincere desire to use the hypocrisy and ambivalence that permeate these performative acts of exploitation is indeed reflected here in the coopting of this luxury tourist industry. This double antagonism is the sort of unease that has become synonymous with Sierra’s practice.

Ultimately, while asserting that “the anarchists are right”, Sierra concludes that “if being an anarchist means taking a moral position, then I cannot consider myself an anarchist”. To its credit, Black Flag has a clarity of political affinities and a sharpness of message hardly if ever encountered in the mainstream art world. Perhaps only through such a grandiose action could the awareness of the art-consuming public be invaded. Was it worth it? The answer depends on how many of those who experience Black Flag draw inspiration from its beauty to practice refusal and think critically towards all oppressive power and every state.

Suggested

States of Violence

In collaboration with WikiLeaks

HOW TO SAY IT THE WAY IT IS

Rua Red

US OR CHAOS

BPS22

ORDER

Democracia

KHAM: THE ROAD

PETR DAVYDTCHENKO

TESTOSTERONE

COUCOU BEBE 75018