PORNOPOLITICS AND OTHER PRECEDENTS

Pyotr Pavlensky

Artist Statement

Subject-Object Art is based on the existence of the phenomenon of power. Power is control and governance. If power stops controlling and governing, it stops being power. Consequently, two components are necessary for power to exist: those who govern and those who are governed. These two components are called the subject of power and the object of subordination.

THREAT

Event: 09.11.2015 | Sentence: 0 years | Time served: 7 months | Fine received: ₽981,500 | Selection of precedents: 2016

"Russia has ordered that a performance artist be jailed for 30 days pending trial after he set the doors of the FSB security service in Moscow on fire in a political protest." THE GUARDIAN

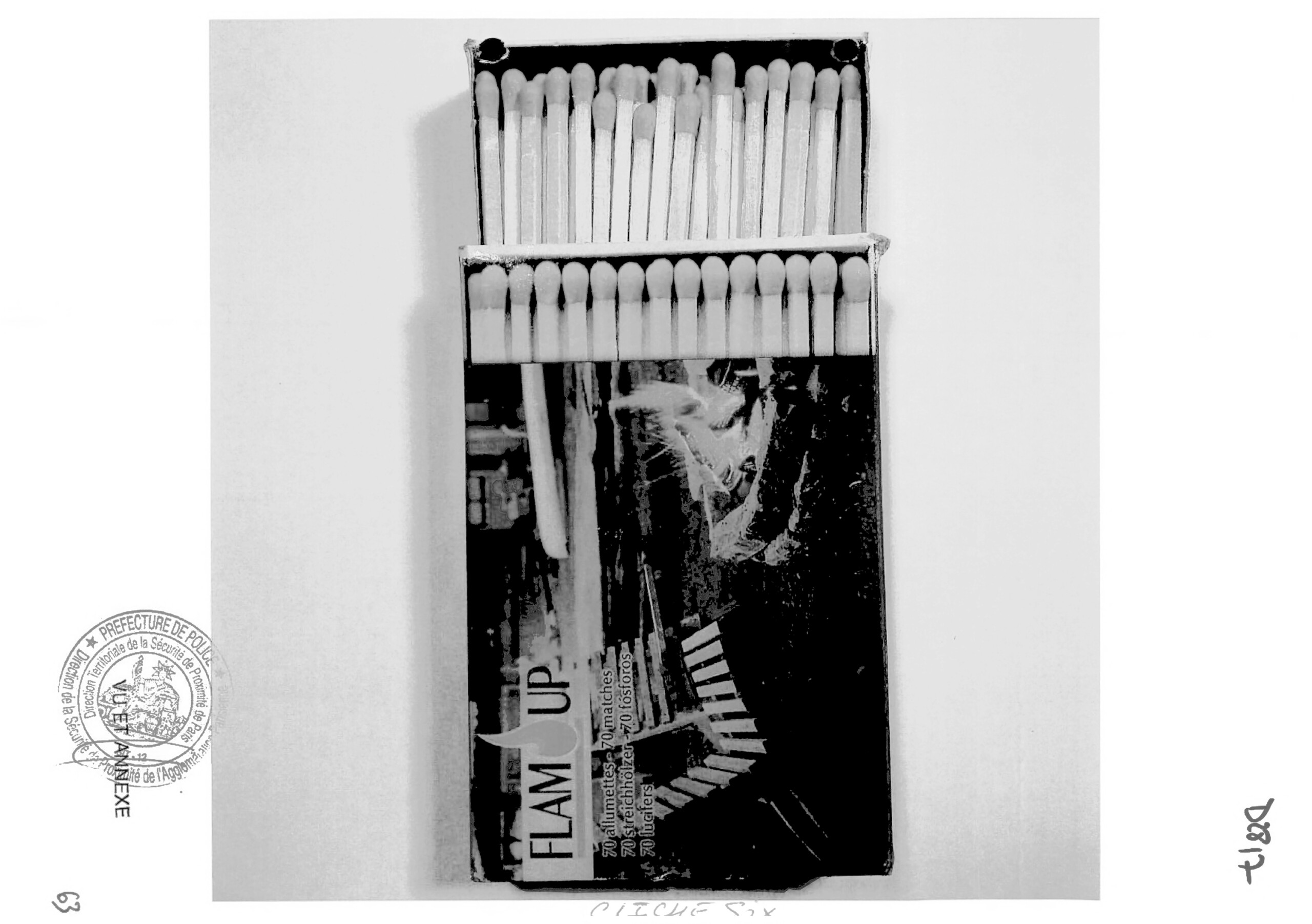

LIGHTING

Event: 16.10.2017 | Sentence: 3 years | Time served: 11 months | Fine received: €21,678 | Selection of precedents: 2018

"Russian Artist, Sentenced Over Bank Fire, Dedicates Trial to the Marquis de Sade." THE TELEGRAPH

PORNOPOLITICS

Event: 12.02.2020 - 15.02.2020 | Sentence: ONGOING | Time served: ONGOING | Fine received: ONGOING | Selection of precedents: 2020

"Controversial Russian artist in court for posting sexual images of Parisian mayor candidate." EURONEWS

Installation Images

Essay

P.

By Jenny Doussan

1. The agents of the law are the artist’s collaborators.

‘The anonymous scribes, the insignificant functionaries who wrote these notes certainly had no intention of either knowing or representing these men: their only aim was to stamp them with infamy.’ – Giorgio Agamben, Profanations

Pyotr Pavlensky is an infamous artist. His work is characterised by its encounter with the law, its criminality, whether this criminality be that of the hallowed dissident or of the anarchist pariah. Pavlensky’s infamy is not the mark of persecution. It is the very foundation of his work, which the artist defines as Subject-Object Art. The artwork is produced in its confrontation with the state, in which the roles of the powerful subject, the state, and the subordinate object, the artist citizen, are inverted.

This inversion is not a matter of mere appropriation or swapping places. It is closer to the ecstatic moment of a sadomasochistic encounter. Pavlensky contrives circumstances in which officials engage in the creative process at the very instant in which they attempt to suppress it, be it the police response to public disorder, an interrogation, or the production of evidential documents for use in court proceedings against the artist. In these instances, the agents of the state cannot but contribute their labours to the cause of Pavlensky’s art.

With his gestures, as he calls these actions, Pavlensky puts his body into play. He desubjectifies himself before the law, surrendering his body as an object: naked, vulnerable, criminal. But then a peculiar thing happens in the course of the ‘event’, the artist’s term for this orchestration of circumstances. The officials, in their attempts to enact the will of the state as its proxies, not only exert the state’s power but also desubjectify themselves before the law in the process. This moment, the instance of Subject-Object Art in which the juridical ends of the execution of power are no longer discernible, is called the ‘turn-around’. Pavlensky is thus not just playing with the law by appropriating it for the cause of art. He is acting in concert with its agents. The police, prosecutors and judges are all his accomplices, as the distinction between friend and enemy is confounded in the creative act. A new subjectivity surges forth.

2. The law reveals its natural violence, expends itself, and becomes inoperative.

‘That the law is defined as an articulation of violence and justice is an obvious fact that a philologically attentive analysis of the legal texts’ originary formulation makes it difficult to escape.’ – Giorgio Agamben, Karman

The law is in force even when it is not applied. A criminal act is illegal whether or not the crime itself is taking place. The state, as custodian of the law, may prohibit violence but it may also use violence at will to keep the peace. According to the well-known formulation, the state reserves the power to enforce the law by whatever means necessary. There is thus a lawlessness at the heart of the law. Subject-Object Art is contingent upon this dual character of the law, as the agents of the state uphold its sanctity. Pavlensky’s gestures provoke the law to disclose both its potency and its lawlessness, impelling it to expend itself. In the course of an event, in exercising its natural privilege of violence, the law both reveals and betrays itself in just that instant. The artwork thus seeks to depotentiate the state’s power, leaving it inoperative.

This depotentiation occurs in two ways: by exposing lawlessness as the foundation of the law itself, which it ordinarily conceals, and subsequently making visible an alternate use of this means, which it ordinarily instrumentalises. This movement does not just affect a reversal of roles between subject and object, master and slave, it decouples the articulation of violence and justice and confounds the poles of law and freedom. It brings forth the inoperativity that always already exists alongside operativity. In its play with the law, Subject-Object Art nullifies the original ends of the police intervention even as the artist remains at the mercy of the law.

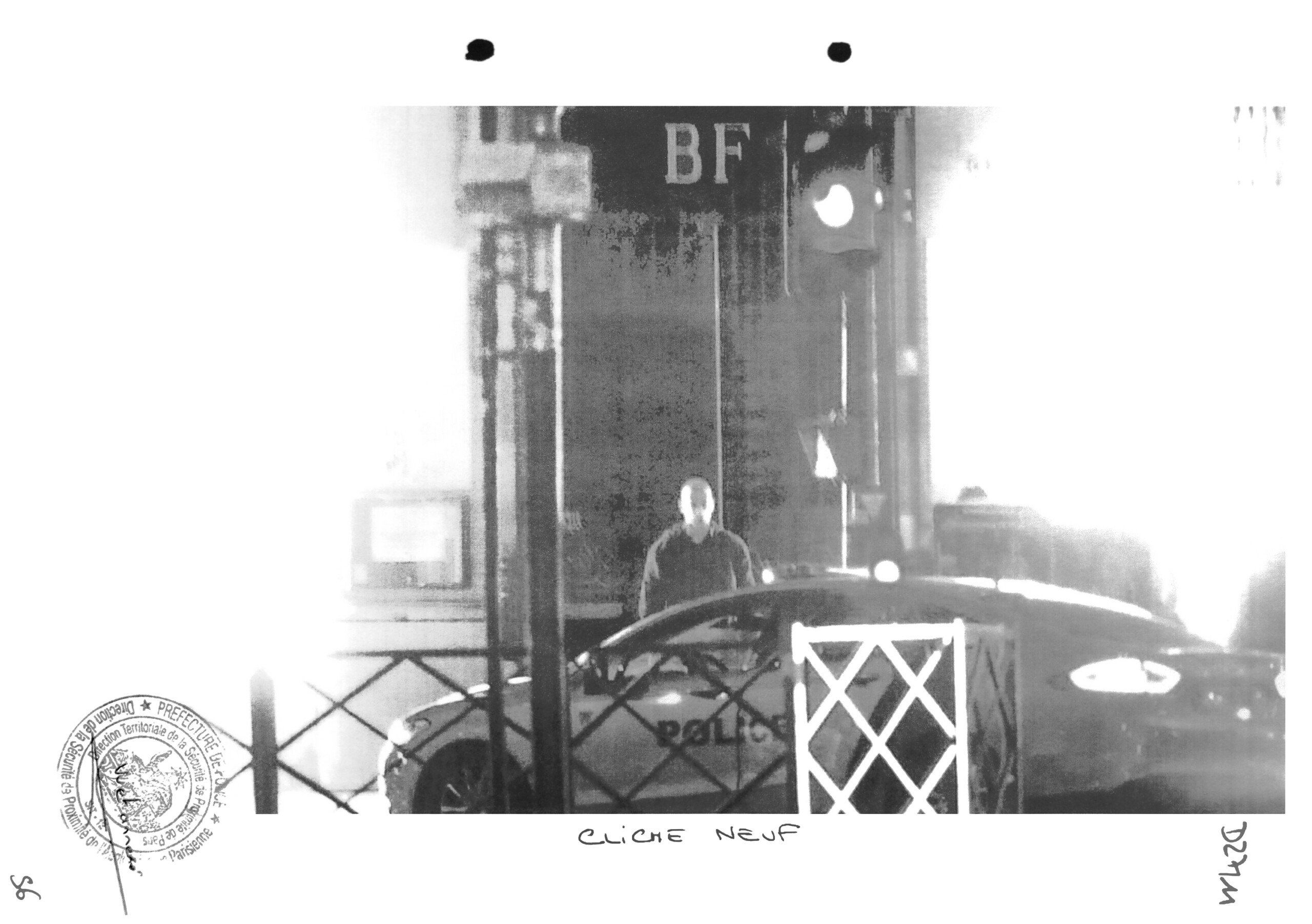

3. The state is capable of producing beautiful images.

‘Just as, in the gesticulations of the mime, the movements usually directed at a certain goal are repeated and exhibited as such—that is, as means—without there being any more connection to their presumed end and, in this way, they acquire a new and unexpected efficacy, so too does the violence that was only a means for the creation and conservation of law become capable of deposing it to the extent that it exposes and renders inoperative its relation to that purposiveness.’

– Giorgio Agamben, Karman

In a popular American television drama of recent decades, a large poster of the mugshot of Frank Sinatra, arrested in 1938, appears in the background on the wall of the centre of operations for a mafia boss. The image is beautiful, not in spite of but because of Sinatra’s depravity, which is precisely why it appears in this setting. The photograph is testament to the law’s proclivity for the aestheticization of its transgression, just as it is testament to the necessity of the state to mythologise crime. The mugshot thus enhances the prestige of the police even as it operates as a judicial instrument. It is therefore a means to an end that ultimately upholds the mystique of the law even as it glamourises the criminal.

Pavlensky’s art practice recognises the capacity of the state for aesthetic invention. It provokes agents of the law to participate in the fabrication of beautiful images, which he terms ‘precedents’. Unlike the Sinatra mugshot, which—beautiful as it may be—merely serves to uphold and even enhance the power of the law, Pavlensky’s precedents are a collaboration with state officials that do not mythologise the law and its obverse, crime. The precedent, rather, extracts the beautiful image from its context as a judicial instrument. As its name suggests, the precedent, as an aesthetic object, is the foundation of a judgement, but one released from the nexus of law/criminality.

4. The artist and the law are united and liberated in play.

‘Politics and art are not tasks nor simply ‘works’: rather, they name the dimension in which works—linguistic and bodily, material and immaterial, biological and social—are deactivated and contemplated as such in order to liberate the inoperativity that has remained imprisoned in them.’

– Giorgio Agamben, The Use of Bodies

As Pavlensky has said, in Subject-Object Art ‘power works for art’. But then what does it mean to work for art? These words are frequently coupled together but their relationship is complex. Art is just as much the antithesis to instrumentality as it is the product of one’s exertions. ‘Work’, in Subject-Object Art, refers to the creative act. Power, in this sense, labours for art. In the event, this labour enhances the extrajuridical being of the punitive mise-en-scène; in the precedent, it liberates the image from its judicial use so that it may exist freely as art.

This profound yet negligible change is seldom recognised by the sensationalist media apparatus, whose attentions are inevitably drawn to Pavlensky’s sacrilegious practice. This apparatus further does not recognise its own extended role, as another proxy for the law, in the creation of Subject-Object Art. Even in more magnanimous press coverage, the work’s profanity, its true political significance, is not often brought to the fore. This profanity does not consist of mere scandal or even opposition to power alone.

Subject-Object Art’s relation to power is political in the sense that it demonstrates its fundamental impotence by giving it a new use. Power must violently suppress dissent because there is no other justification for it to exist. To show this is a political task. To demonstrate it is the work of political art. In Pavlensky’s works, the law finds another use. Police action is not just the exercise of force, it is a tableau vivant. Interrogation is not just a punitive apparatus, it is a dialogue on art. Evidence is not just proof of a crime, it is a beautiful image. This is the profanity of Pavlensky’s Subject-Object Art. In profanity, there is no longer guilt.