TORTURE

Andres Serrano

ARTIST STATEMENT

The story of torture, the act of inflicting severe physical or psychological pain by one human being on another, is as old as the story of the world itself.

While torture was declared unacceptable by the Geneva Convention in 1949 and subsequently prohibited by the United Nations Convention against Torture, the fact remains that at least 81 world governments currently practice torture secretly and illegally, but at times, openly.

With this work I visualize the full spectrum of torture, which is embedded in our society: torture as entertainment and tourist attractions, torture from the perspective of concentration camps and interrogations, torture as capital punishment and modern day recreations of the history of torture.

In doing this, I assumed the roles of both the artist and the torturer. As the artist, I show the audience what I see. As the torturer, I have to think like a torturer and assume control.

It’s easy to torture people when you have power over them.

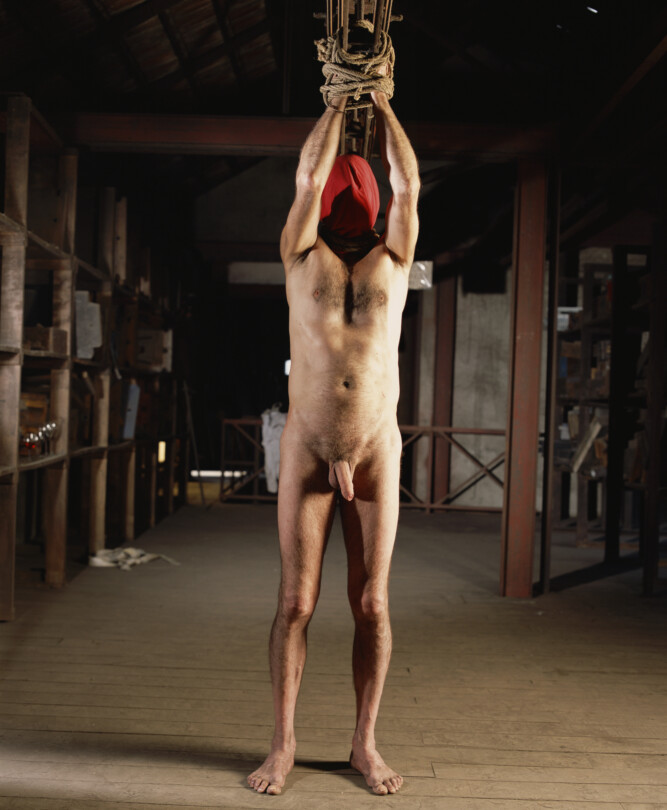

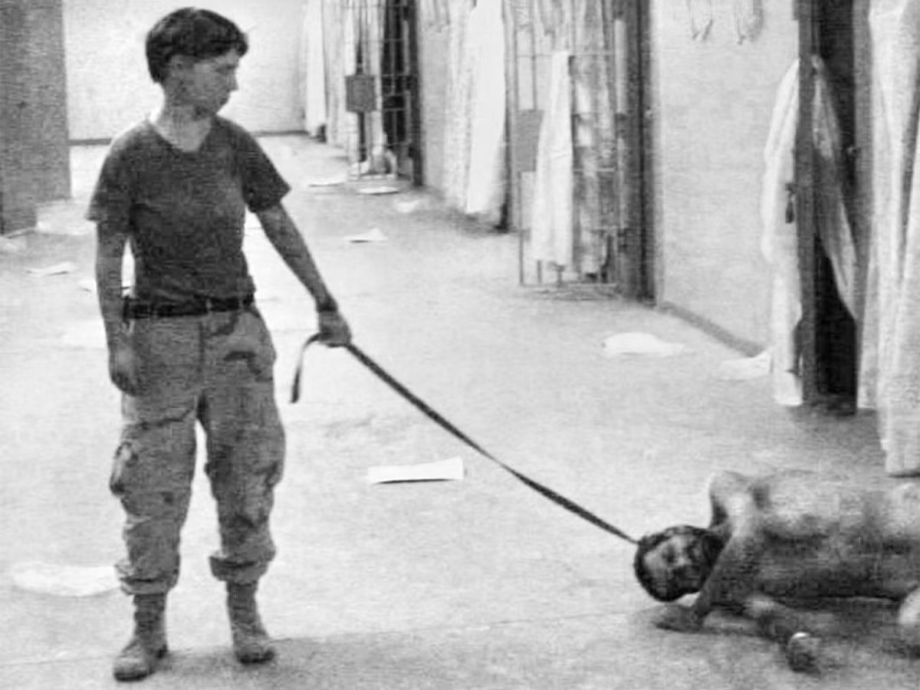

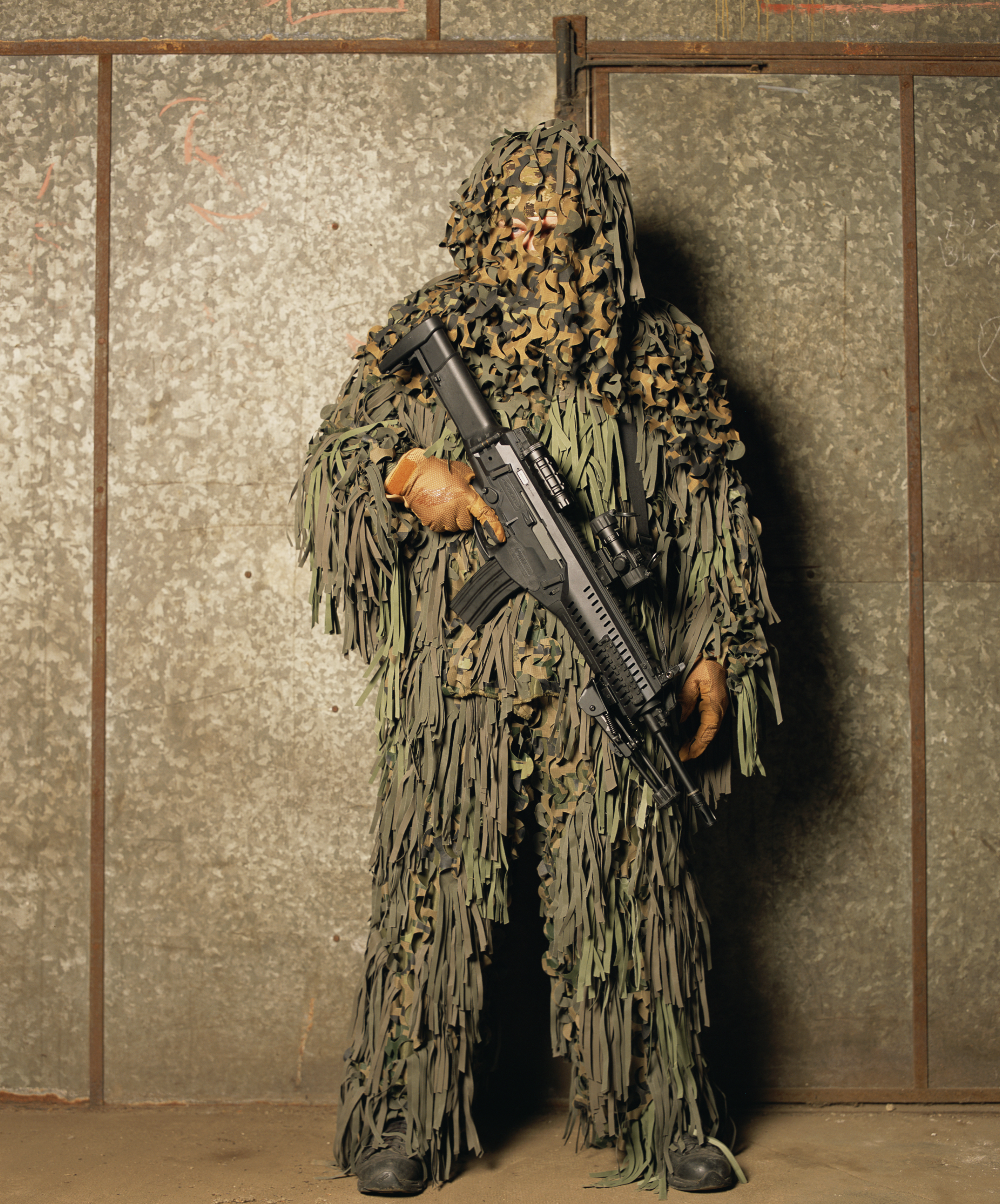

FOUNDRY

"THE NIGHTMARISH IMAGES FROM ABU GHRAIB ARE STILL SEARED INTO THE AMERICAN CONSCIOUSNESS: PILES OF NAKED BODIES, DETAINEES BEING LED ON LEASHES AND U.S. SOLDIERS GIVING A THUMBS-UP AS IT ALL HAPPENS." 'Remember the Abu Ghraib Torture Pictures? There Are More That Obama Doesn't Want You To See' Lauren Walker, Newsweek (2014)

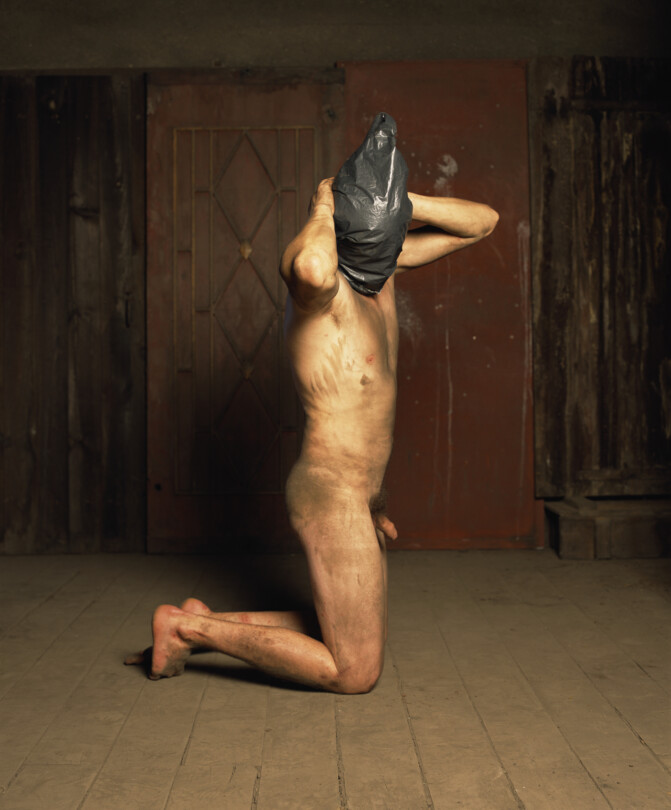

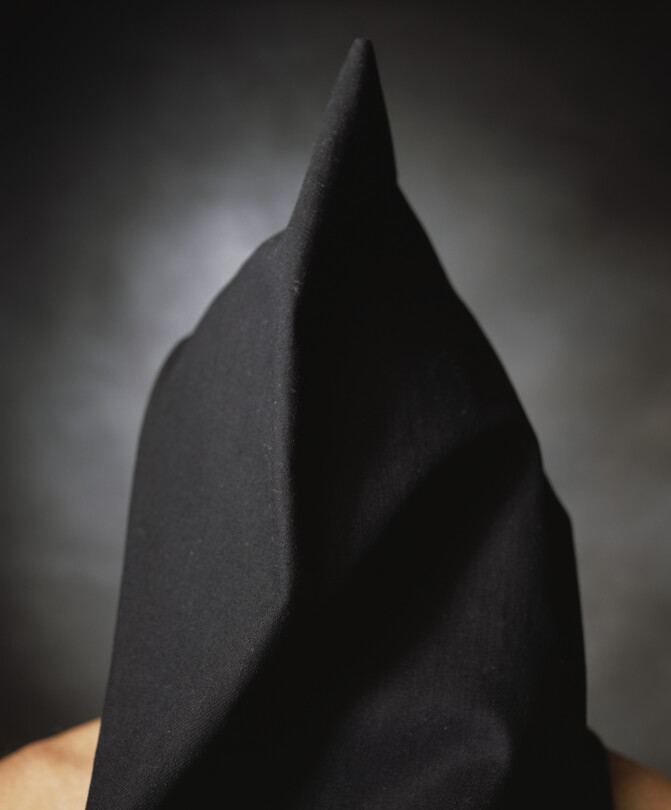

HOODED MEN

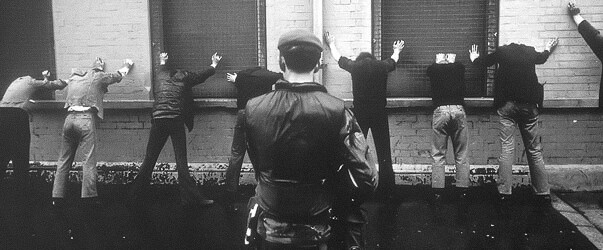

"Throughout his imprisonment, [Brian Turley] was deprived of food, water and sleep, and was beaten and kicked, with police fighting with each other to get a dig at him, in short, the police used Brian as a punch bag until he collapsed unconscious."

Essay

Photographs without escape

By Germano Celant

Representing the unrepresentable, whatever goes beyond every conceivable dimension and ethics, is the area chosen by Andres Serrano for his photography. His entire career is marked by the pictorial portrayal of glowing life moments that seem impenetrable. Events or people, rituals or situations that tell of an incomprehensible and excessive world capable of challenging known standards. An all-consuming quest that does not evade confrontations with reality, even if painful and overwhelming. In this sense, his work has tended to exceed all limits to get closer to a tragic vision, which in its tension leads to a discourse on human beings, of whom a two-faced picture is given. His photography is thus an interrogation and a meditation, religious in nature, to get a grasp of the mystery of life and its extreme manifestations, from sex to politics, from living to dying. It focuses on resolving the coexistence between the carnal and spiritual, between sex and chastity, between the sacred and profane, between heaven and hell: Heaven and Hell, 1984.

An almost transcendental adventure, which explores the negative and its content while challenging viewers with strong images, from The Morgue, 1992, to A History of Sex, 1996, which takes upon itself the sulphurous side of suffering and pleasure. For Serrano, the task of art is to document horror with its sinister splendour and the equally terrible aspect of society and morals. He ran the risk of falling into diabolic poetry with Piss Christ in 1987, but he used it to define a dazzling moment of a sacred ideal, as well as its symbolic power. He playfully surprises by balancing two opposing forces, urine and the crucifix, to surprise and astonish. The image that is established, is as a rapid and unpredictable event, leaving people aghast. It is established as the link between a splendour illuminating the dark dimension of existence, as well a visual weapon to awaken those who tend to avoid its terrible expression.

As the artist portrays the silent, menacing existence of the Klan, 1990, he tends to elicit a tension, because it highlights a world populated by disturbing and enigmatic figures. He makes it a tool of emotional exhortation, that aims to divert the public’s attention from the hypnotic embrace of things and images connoted by an aesthetic futility, making them insignificant and decorative. Serrano pushes the observer towards hell. He feels the responsibility to obstinately highlight the alien and horrific dimension, which permeates society. He wants to communicate a fragment of this, by revealing it and making it visible, even if unrepresentable, because it goes beyond any condition of feeling and experience. It is a work ethic that in its excessiveness is not accepted, but cries out in protest and outrage. It is evidence of his contradictory power, connected to the experience of horror that is factual not conceptual. His photographs exhibit what purely exists and don’t require theoretical or literary recognition. They are images without escape.

Serrano’s photographs are also frontal, possessing a strange force that attracts and immerses viewers in a disturbing and dramatic landscape. They dominate viewers, causing them to pass from a passive cognitive condition to an emotional one. All this is due to the accentuation of evil and suffering that accompany the mode of sacrifice, Heaven and Hell, as well as breakup and destruction, The Mourge, against which all human resistance crumbles. It is almost a vicarious suffering, in search of a personal leveling off that we can connect to his religious education, where suffering and pain have a purifying value. It is a vindication of artistic pietas, as a vindication of a creative raison d’etre. This turns out to be a countervailing process towards his own arrogance, which can be countered only by an active exercise of show, with no religious or philosophical, or aesthetic or moral qualms – the devastating power of evil.

A new step towards photographic temerity is undertaken by the artist, by proceeding to another abysmal place, that of excessive human conduct associated with the evil gratuitousness of executioners’ mistreatment and behaviour, the authors of tortures and killings. A love of the pleasure of offending, humiliating and destroying, that defies comprehension and is still opaque in the visual mode of communication. In fact, there is no photographic evidence of such inhuman procedures. They remain testimonies of survivors, but they are unimaginable since they are undocumented. With his new series Torture, 2015, Serrano tries to force you to identify the places and practices of death that were professed from antiquity until recent years. He enters into buildings of pain and suffering, from Mauthausen in Dachau and Buchenwald, where survivors leave their mark with mere fragments – writing and clothing – of a brief existence before a tragic fate, or it is testified to by the machinery of extermination and incineration, testimony to the maximum degradation of European culture. He does so with extreme detachment, as if to abolish all personal feeling, to document the brutal coldness of the almost metaphysical void that circulates in those cursed spaces.

Since it is not possible to capture the perpetrators on film, photography takes hold of the victims’ silence. Alongside their fate, everything of a personal nature appears useless, unnecessary and misleading. Communicating a will to destroy, and therefore snuff out life, is reflected in the nothingness, or emptiness, of the rooms, the cells and the corridors. It is the same emptiness that fills the impersonal, standardised furnishings of the buildings in Eastern Germany, where political prisoners were interrogated by the Stasi. The architecture contains fragments of experience, ranging from the solid presence of walls to the horrific density of torturous and exterminatory practices. Serrano’s photographs are established as the symbols of the absence and the impossibility of “representing” the human suffering associated with ideological exaltation. The artist then proceeds indirectly, to use the image of the concentration camps to affirm a presence arising from the unconscious, so that the vacuum is affirmed as an utterly tragic image of extermination and genocide, in which civilisation founders.

If the incomprehensible is invisible, its extremism may rely on the social and instrumental apparatus of its progress, testifying to the cruelty of the perpetrators of evil and horror. Serrano finds resources which are figurative and iconic, historical and current, in historical and consumerist museums, as well as in accommodation and detention centres for migrants, political refugees and people suspected of terrorism. The latter is architecture – in the UK and Ireland – purged of all traces of blood and pain, linked to the treatment of detainees suspected of activities subversive to the state. They are minimal places, where there does not appear to be any time to represent the torture practiced and suffered. Yet, they have experienced lacerations and wounds, blood and faeces, defining the face of the demonic, repressive and punitive structures promoted by the British government. Serrano’s photographs try to define, even here, the periphery of nothingness, where space has faded the omnipotence of evil and brutality.

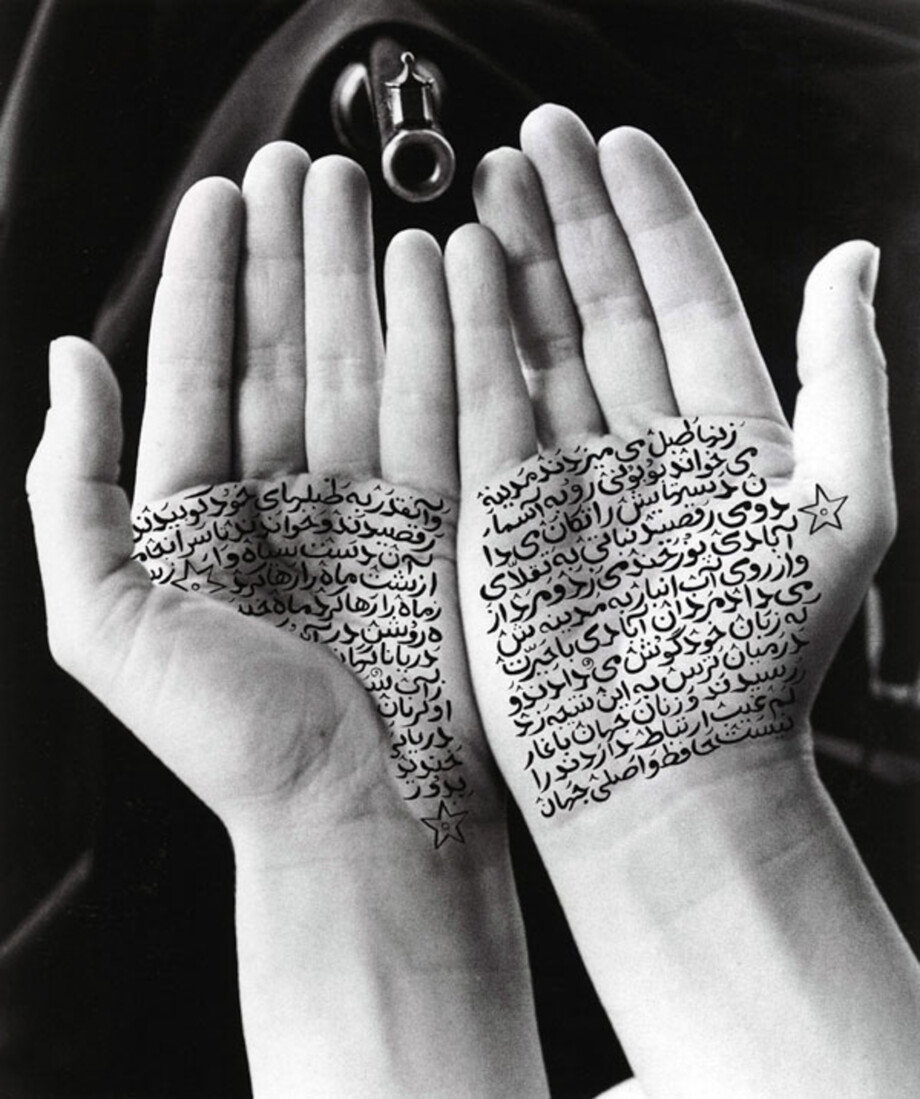

However, the large silent spaces and architecture only serve to produce the mirror situation, to duplicate the distressing void of thought associated with the Holocaust or the tragedy of people fleeing war and famine. Here no real “experience” materialises, meaning Serrano realises that the only way to get close to the pain and suffering is by making a huge leap: he comes in contact with the victim and attempts to draw near to the torturer. Herein lies the real depth of suffering, both as the sufferer and as the inducer of pain. In the first case, he approaches and enters into dialogue with Fatima, 2015, and shares her sufferings and humiliation. He records orally her abuse in Sudan, who as a prisoner, was raped and humiliated. Disgusting and cowardly actions, that leave moral and physical marks, but in Serrano’s portrait, they are just guessed at through the muted silence, and the terrible agony that hide under her yellow veil. The same procedure is adopted in The Hooded Men, 2015, using a black hood, which recalls the one used for the prisoners in order to subject them to loss of orientation and time. These portraits are also dramatic in the way they obliterate the face, resulting in the nullification of identity, as practised in Ireland by British military torturers. A denial of physical appearance, with which the face reflects a human being’s soul, becomes instead disturbing when it is a diabolical and monstrous likeness of those responsible for such brutal interrogation procedures and physical isolation: John Kiriakou, Former CIA Officer. Whistleblower, 2015. With these “shots” of the degradation process repeated on the same people who have been subjected to it, the artist seeks to express bodily shades of suffering which have no public expression, and are therefore eliminated, creating a reflection on the intimacy denied and destroyed.

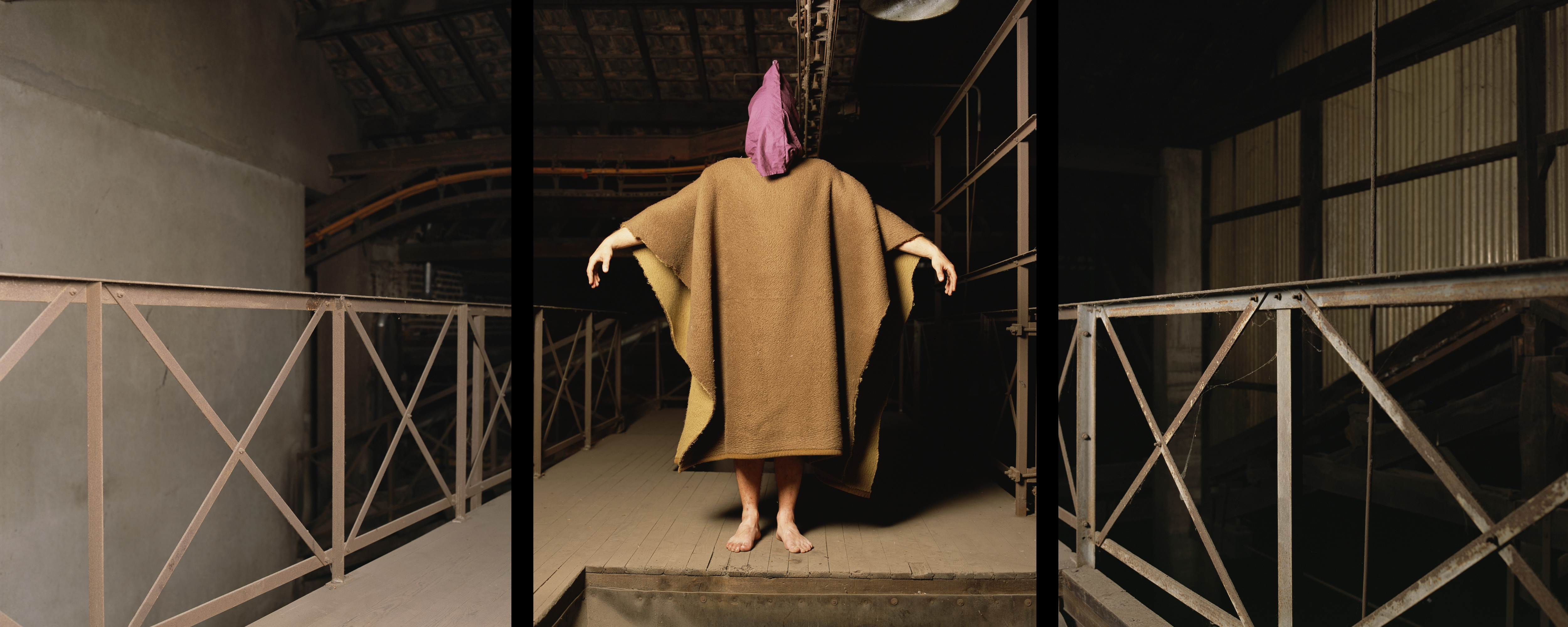

Not being able to empathise physically and bodily with the victim, because his pain affects him only from the outside, Serrano tries to take into account the role of the executioner and torturer. He chooses a possible identification with its practices, by focusing on the masks and equipment used by the inquisition to extract confessions from alleged witches and nonbelievers: terrifying and repellent instruments collected in different institutions, museums and castles, often original or reconstructed, with the corresponding execution scenes, including human figures. The artist studies and lists the instruments typical of torture, and draws a figurative and narrative dimension from them which translates as realist, albeit simulated, “representations”, where the human body is, however, virtually humiliated, so as to communicate the experience of torture. It is a way to make its figural and environmental excess unavoidable, so as to stage the absolute terms of this inhuman process. With this series of pictures, he seeks to obtain a state of reality, in order to communicate a totally sensory and emotional experience. It is an orchestration which feeds off the brutality of a space, The Foundry, where weapons of death were produced, so as to close the circle of the passing of evil. It is the awakening of an industrial nothingness, where the human suffering of war and labour and politics and hatred lie forgotten. Systems of denial that Serrano recalls through his representations which function as a critical reading of destruction that are stimulated by the pleasure of offending and hurting.

© 2015, Germano Celant

Suggested

INSURRECTION

Andres Serrano

THE GAME: ALL THINGS TRUMP

Andres Serrano

PISS CHRIST NFT

Andres Serrano

US OR CHAOS

BPS22

HOW TO SAY IT THE WAY IT IS

Rua Red

KHAM: THE ROAD

PETR DAVYDTCHENKO