GO AND STOP PROGRESS

Petr Davydtchenko

"I live like a token in the crypto-ecosystem. Decentralised, semi-autonomous and not governed by past hierarchies." Petr Davydtchenko

Essay

Roadkill — a Symbol of Our Relational Reality?

By Dr. Aneliya Bakalova

Clinical psychologist and forensic psychotherapist-in-training, working for the NHS

Petr Davydtchenko makes a clear statement about the personal philosophy that underpins his experimental lifestyle: “I look to find a parallel system, to see if it’s possible to exit the current capitalist system” (‘Meet the artist starting a roadkill-to-table revolution’, 2019). He openly rejects “modernity”, with its inherent social, political and moral codes and hierarchies, and endeavours to pursue “a semi-autonomous and non-governed way of life” (‘It’s not about shock value’, 2019). His opposition to what he calls “modernity” is most strikingly expressed though his choice of food: roadkill and whatever nature has “discarded”. It’s interesting to notice our immediate visceral response to this “alternative” way of living: shock, disgust; yet not too far behind this comes the question about the relationship we – the “modern” members of society – have to food.

Feeding and being fed – a triangular relationship Davydtchenko’s three-year experimentation with this lifestyle places his relationship with the food he eats in order to survive at centre stage. He feeds himself with roadkill, roadkill supplied by the modern world.

Our first contact with food, is always mediated by another – first the Mother, whose womb is the environment within which

the foetus develops, the environment that feeds the unborn through its umbilical cord. Then it is the mother’s breast, whether in literal terms, or through the hand that holds the milk bottle or feeds the baby food in any other form. The point is that feeding always involves an interaction with another. States of hunger evoke very powerful emotional responses in babies, which are “detoxified” (Bion, 1965) or “contained” by the [m] other gradually; these exchanges form a crucial part of the foundations of human personality and the way the individual will come to interact with the world around them, human- and other-than.

In a “good-enough” relationship to the breast/mother/caring environment, the infant gradually shifts from the pleasure principle (i.e. the absolute need to have all its needs gratified as soon as they arise – including the need to be fed), to the reality principle (i.e. learning how to tolerate the state of frustration and accept the limitations of the external environment, inherent to which is an appreciation that the environment is external and separate to the infant) (Winnicott, 1953).

Further, the baby learns how to regulate its emotions through them being met and responded to by the mother (it internalises the soothing and nurturing function of the mother), and learns to trust that its needs, for food included, would be reliably met even if it has to wait and tolerate moments of frustration. This set of relational transactions inevitably involves food as a currency of sort, something that can be experienced as rewarding and nurturing, but that can also be used as punishment, withheld, presented in an unsatisfying form or, in extreme cases, used in cruel and abusive ways.

Who is the feeding other in Davydtchenko’s practice? I will now explore the symbolic meaning of the act of the artist feeding himself, and the role of the “other”, by looking at the triangular relationship between the artist, his food, and the “modern” society that “produces” the roadkill.

Ingesting what is killed off, left behind

Davydtchenko does not simply give up food supplied through capitalist systems of production and distribution (buying food with money, whether in a market, supermarket, a restaurant or street vendor). There is more than one alternative to being a consumer in the global food market. He could have started growing food himself, he could have hunted, or he could have gleaned – a practice well-known in France, and depicted in Agnes Varda’s documentary “The Gleaners and I” (2000).

Instead, Davydtchenko makes a deliberate choice to make roadkill his main diet. This involves cycling for many kilometres every day, in search for roadkill corpses; collecting the corpses and engaging in an often-arduous process of checking the meat for disease, storing the meat, skinning and dismembering it, when it’s time to cook, and finally – preparing a meal and eating it.

Moreover, Davydtchenko takes photos of the roadkill he finds, and documents the location of each find; he later also records the recipes he uses when cooking the meat, and refines his cooking skills by being taught by experienced chefs. The process of documentation, particularly of the corpses as found on the road, strangely resembles forensic photographic evidence. The artist shows little to no emotion when talking about this practice – it is turned into a routine devoid of sentiment, one that resembles being in an boot camp.

This emotional detachment from the roadkill Davydtchenko eats contrasts sharply the visceral feelings evoked in most of us when we hear about the project: shock, disgust, repulsion. The image of a local kid looking for its lost cat, only to find it in the artist’s freezer, is particularly emotive. The artist goes as far as stating that his ultimate goal is to open a roadkill restaurant and achieve “three Michelin stars for cooking donkey penis” (‘It’s not about shock value’, 2019).

The relationship between the artist and his food thus remains obscure. This invites the audience to interpret his “art” in multiple ways – as an appropriation of the same relational values characteristic of capitalist societies– in order to expose their absurdity; or as a complete rejection of those values and exposure of the damage caused by “progress” – ingesting what has been rejected and discarded.

“Eating kittens and raw rats” is presented as a central part of the artist’s alternative way of living, one that is meant as a counter culture, counter-life-style to “modernity” and the Western idea of “progress”. What is the symbolic meaning of the act and products of roadkill, and how is the artist appropriating this to express his own socio-political position in relation to modern capitalist societies and the notion of “progress”? I will now turn to exploring the relationship between “modernity” and “roadkill” in order to address this question.

The feeding other: “modernity” and roadkill

One of the first videos I saw from the archive was of a Pitbull corpse on the road, run over by cars, every few seconds. The bloody flesh, hit and run over repeatedly, was difficult to watch for longer than a few moments.

10.

- 9.

This, as well as the “crime-scene-like” collage of run-over animal corpses on Davydtchenko’s wall, triggered questions about how we understand “violence” and “aggression”. One can hardly ignore the presence of the word “kill” in Davydtchenko’s main diet.

The term “roadkill” sounds strikingly unspecific and technical. The Oxford English Dictionary defines roadkill as: “Animals killed on the road by vehicles” (Dictionaries, 2010). It refers to a group of animals, who, based on the location might include anything from domestic pets (cats and dogs), to domesticated cattle, and wildlife. By denoting a heterogeneous group of animals with one term, “roadkill”, we create an emotional detachment and disinterest in what the killing of these animals means: both sentimentally, as well as with regards to their place in the ecosystem.

Furthermore, the accidental running over of animals in not a criminal act. In a recent review of the US environmental history of roadkill, Gary Kroll notes that “road-killed animals are simultaneously one of the most common ways that Americans encounter wildlife and one of the most unexamined phenomena by scholars” (Kroll, 2015). The author notes that “early roadkill mitigation techniques” focused on making the roads as uninviting to animal mobility as possible”; this later shifted to designing “permeable highways” which allow for animal mobility and aim to minimize “the impact of habitat fragmentation” (ibid). Kroll further quotes statistics about the number of deer killed by road traffic in the US every year (one-two million), and the estimated cost of such collisions (over 8 billion USD according to a 2008 study). The author proceeds his exploration of the American

history of roadkill, but surprisingly sates early in his text that the focus will not be on how humans have “changed their attitudes toward animals as a result of their daily commutes and annual vacations”, due to the “methodological obstacles” involved in exploring this question (ibid). I invite the reader to consider the relationship we, “modern citizens” of the developed world, have to the roadkill animals.

The act of “killing” when human beings are concerned, carries varying degrees of intentionality. Hence the use of different words to denote a death caused by another, where such intentionality is judged to be absent. In such cases we talk about manslaughter: “The crime of killing a human being without malice aforethought, or in circumstances not amounting to murder” (Dictionaries, 2010).

The act of roadkill, it could be argued, also lacks “malice aforethought”. It is something that just happens, a by-product of modern life, an unfortunate coincidence. What can we learn about our individual and collective nature, by looking at the phenomenon of “roadkill”?

Ecologists and eco-psychologists (Dodds, 2011; Totton, 2011) change the language used to describe the non-human environment, by abandoning the prefix “non-”, which suggests a hierarchical relationship, where “human” is superior (the alternative being the negating “non”). The terms “other-than-human” and “more than-human” are used instead. This subtle change gives away the different value we attribute to other-than-human forms of life: we order species hierarchically, and often based on the monetary and/

or sentimental worth they carry. For example, the loss of an animal might be experienced as a loss to humans, if that animal provides meat classed as “high quality”, or if it provides other materials, such as milk, fur, skin or fat that can in turn be transformed into commodities to be sold and profited from; in other cases, such as pets or game, animals are used to provide company, emotional comfort and entertainment.

This way of relating to the animal-, and other-than-human world, resembles what the psychoanalyst Melanie Klein coined as “part object” relationships (Klein, 2012). She developed this term to describe the baby’s experience of the mother not as a separate being in her own right, but as an extension of the baby, a part

object which is there to provide gratification as and when needed; conversely, the failure of the part-object to satisfy and gratify is experienced as a “bad presence” or as a persecution. This way of relating, characteristic of very young infants (< 6 months old), is called by Klein the “paranoid-schizoid” position (ibid). In normal human development, we start to gradually learn that there is a reality existing outside of us, starting with the realisation that [m] other is separate and that immediate and unlimited gratification is not possible. The same realisation continues to then extend to the child’s growing awareness of the wider social environment, and should ultimately include the other-than-human environment. In what Klein labels the “depressive” position, we can experience guilt in relation to our capacity for aggression towards the [m] other; the guilt, when tolerated, can make way for deeper feelings of concern to emerge, together with the wish for reparation and the capacity for loving and caring feelings (Klein & Riviere, 1964). This

can only take place if we are able to tolerate the frustration of our needs, wishes and desires not being met at all times and at any cost.

What type of relational dynamics does the phenomenon of roadkill brings into light? Automobiles are a signifier of modernity; we need them in order to travel, transport, and often as a display of material success and social status. Yet, by driving those same vehicles, we kill. Is this an act of violence towards the other-than-human? And if so, why are we apparently so emotionally detached from it?

The psychological process named “disavowal” might help us answer this question. It was first used by Freud in some of his key case descriptions such as the “Wolf Man” and his paper on “Fetishism” (Freud, 1918; Freud, 1928). In using the term “disavowal” Freud describes “a vertical split of the ego”, resulting in one part of the mind knowing something, whilst another part of the mind remaining completely unaware of it, in order to minimise psychic discomfort, anxiety and even terror.

Ecopsychologists and psychoanalysts (Dodds, 2011) use the concept of disavowal to explain why humanity is failing to acknowledge and respond to the environmental crisis facing us and threatening our existence. Disavowal reduces anxiety in the face of real or imagined conflicts and crises, such as the collapse of the ecological environment. Disavowal can also be what is in process when we so blatantly turn a blind eye to millions of fellow human beings suffering, as well as when we refuse to really know (intellectually as well as emotionally) about mass inequalities, racism and the various forms of human and animal exploitation,

- 12.

feeding our “modernity”. The problems are not only immense, they require us looking at our own capacity for destruction, and facing what might feel like overwhelming levels of guilt and powerlessness. Turning a blind eye both protects against such feelings as well as allows the more destructive parts of our nature to govern our behaviour.

The psychoanalyst Sally Weintrobe, alongside interdisciplinary scholars, look further into the ecological collapse we are facing and the individual and collective processes that allow for the danger of extinction to remain inadequately responded to, or even fed into. Weintrobe’s paper titled “Engaging with Climate Change Means Engaging with Our Human Nature” explores in particular how neo-liberal ideologies and their realisation in capitalist societies promote certain types of “attachments” to human, and

The ecological debt or “karma” each of us accumulates when shopping for pre-packaged food in supermarket shops is far bigger than that of Davydtchenko and his roadkill diet. Is this alternative the artist’s way to take personal responsibility for his relationship with the environment? Interestingly, I have never heard him talk about this, or link the two. Or is it a gory and shocking way to force us to look at what we are so invested not to see? Like a scream right down from the guts of nature.

Relationship between the artist the “modern” world Davydtchenko states clearly that he would like to develop a way of existence that is parallel to “modernity”. What makes the artist so invested in finding “another way” and thus denouncing “progress”?

The sociologist Robert Merton (Merton, 1968) suggests that

- 14.

other-than-human others; these attachments are characterised by feelings of arrogance and entitlement, as well as corporate greed (Weintrobe, 2010). Weintrobe further states:

“We are most likely to cut off concern and empathy when we convince ourselves that we are superior to those we consign to out-groups that we experience as far away from us; it tends to make it far easier to exploit our out-groups, both human and animal, when we see them as inferior to us and therefore not worthy of our concern” (ibid).

The capacity for mass destruction in the name of obtaining political power, and how that relates to our notion of “progress” was explored by the philosopher and political theorist Hannah Arendt nearly 50 years ago. In her book “On Violence” she wrote:

“Not only has the progress of science ceased to coincide with the progress of mankind (whatever that may mean), but it could even spell mankind’s end, just as the further progress of scholarship may well end with the destruction of everything that made scholarship worth our while.” (Arendt, 1970)

The question of what we qualify as “progress” or “modernity” is surely a complex one with no single answer. It is not my aim to denounce “progress” as something purely bad; what I am highlighting here, just as Arendt did in her writing on political violence not long after WWII, is the price we all pay collectively in the name of progress, and the price that other “non-modern” social groups, as well as the other-than human environment pay. Roadkill is one example of the many costs involved.

marginalised groups take one of three possible positions in response to the mainstream culture they are being excluded from: 1. Adopting the same values of financial success as the main culture, but being denied equal access to education and employment opportunities, attaining success through illicit means (i.e. crime); 2. Becoming “rebels” and rejecting the goals of success and conventional ways of reaching those, by becoming “drop-outs” and creating alternative ideologies and lifestyles; 3. Becoming “retreatists”, thus renouncing any wish or hope for success and withdrawing from society entirely. Davydtchenko could be seen as belonging to the second group – creating an existence adjacent to “modernity”, whilst trying to live by his own “philosophies”.

Davydtchenko’s lifestyle could be seen as further challenging the “civilized” by tapping into much deeper, unconscious human anxieties, the ones linked to “… our civilisation’s ambivalent relationship to the other-than-human world, the ‘primal uncanny’ of nature” (Dodds, 2011, p. 115). His practice could be seen as reversing what is considered to be at the heart of primitive anxieties linked to the animal world (being bitten by a horse, chased by a wolf, “having one’s bowels gnawed by a rat” (ibid, p. 117): he becomes the one who disembodies, skins, ingests. Anne Smelik, quoted in Dodds (ibid) describes the “true horror of the male monster” as lying in the alignment with what is considered counter-phallic, or counter-masculine: “woman, animal and death”. Davydtchenko’s practice certainly involves a daily exposure to the latter two, which raises the question whether he thus challenges and denounces “the male symbolic order”, as represented in the food-chain hierarchy topped by man, and ruled now almost universally by corporate empires.

The wider, ‘holding’ environment

Davydtchenko’s roadkill lifestyle is far from existing in a vacuum. He lives at The Foundry, a residential art-production and exhibition space, occupied by a community of artists, whose work carries strong socio-political messages. The Foundry itself is located in a small village in rural South-West France. Local people appear to not only tolerate but in some cases openly support The Foundry with its multiple activities, including Davydtchenko’s way of existence.

Looking solely at the artist’s survival off roadkill risks that attention is paid in a sensationist way only to what feels gruesome and uncanny. Davydtchenko does not reject social relations, he attempts to redefine the terms of his relations – to his food, and to the people who choose to support him, without a monetary exchange forming part of the relationship. Furthermore, his structured, almost ritualistic daily routine and his immediate access to natural environments, appear to create a state of “being in the present”. This resembles much of what forms key part of third-wave psychotherapies applied in the treatment of trauma and mood disorders, such as depression and anxiety. Mindfulness and guided meditation have become part of popular culture in the West, still often packaged and sold at a price. Ecotherapy, meaning forms of psychological therapy that involve the exposure to “nature”, are offered as free treatment in some NHS trusts in the UK. Has Davydtchenko found a personal way of healing emotional traumas that we are all vulnerable to, at varying degrees? And how are we really ought to measure progress: by the degree of expansion and material growth or by the quality of our relationships – with other people, as well as with the other-than-human?

Suggested

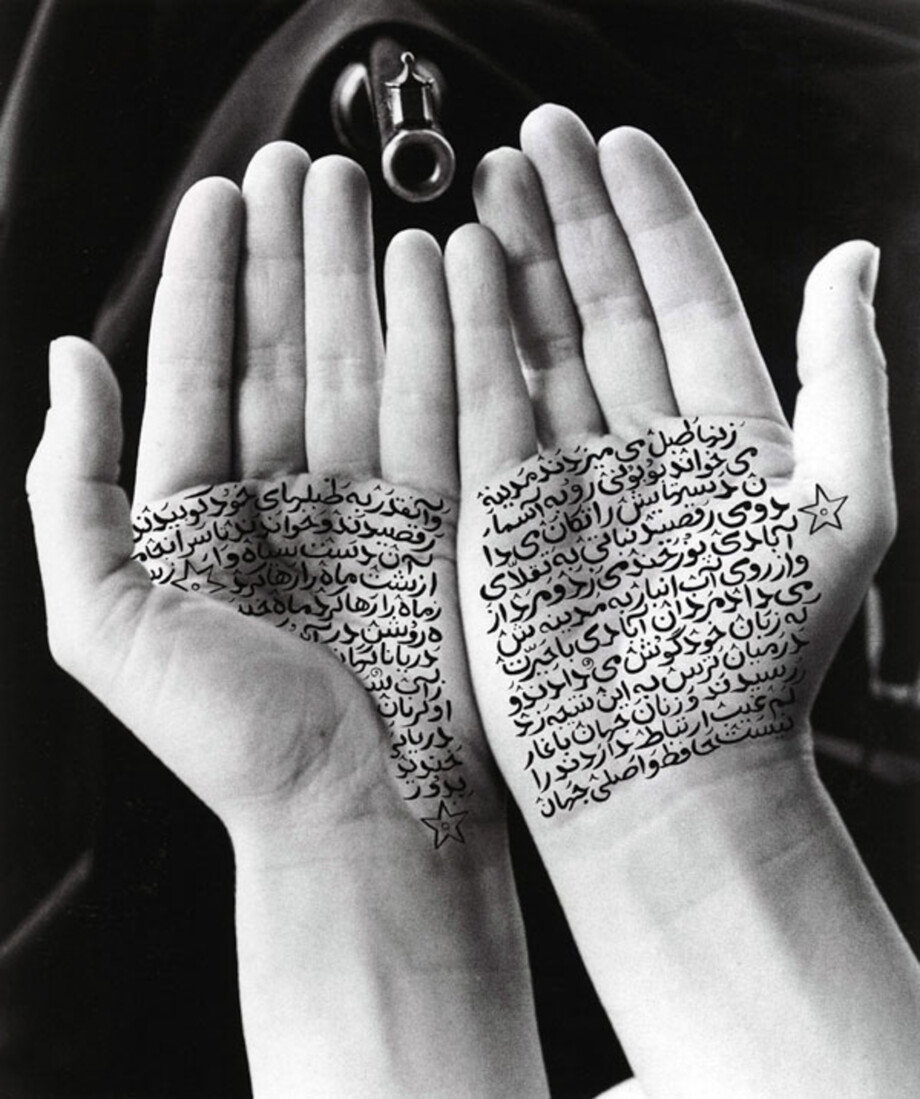

HOW TO SAY IT THE WAY IT IS

Rua Red

US OR CHAOS

BPS22

THE VISITOR

BRUCE LABRUCE

THE DIRTIEST CUP

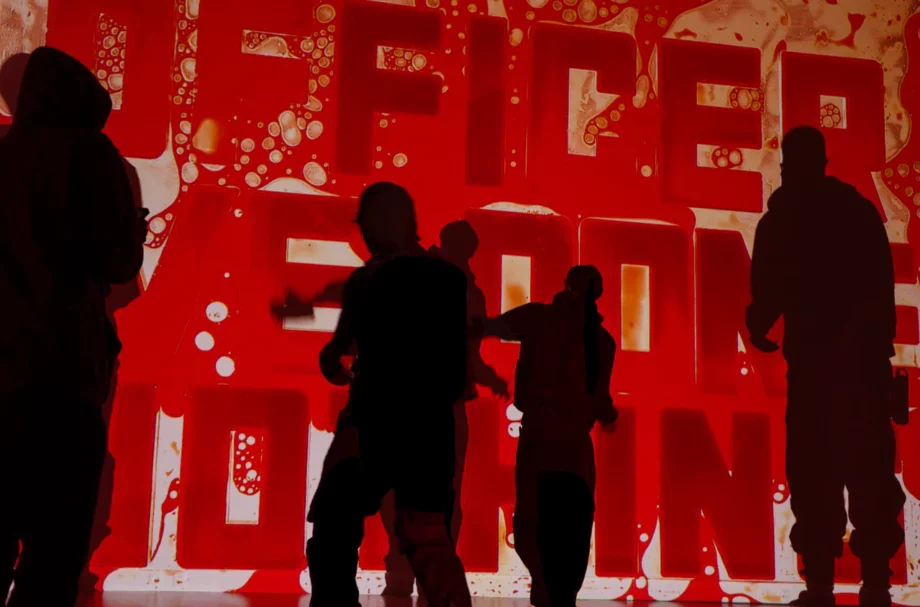

Andrei Molodkin

Political Drills

Andrei Molodkin, Skengdo x AM and Drillminister

States of Violence

In collaboration with WikiLeaks