THE VISITOR

BRUCE LABRUCE

Artist Statement

It makes sense in a contemporary British context to represent the visitor as a racial minority considering the xenophobia and paranoia about immigration currently displayed in Europe, not only by the increasingly vocal extreme right wing elements actually gaining political traction and governmental representation, but more vaguely by traditionally colonialist countries in general that have previously “invaded” other countries of different ethnic majorities as hostile “aliens” themselves.

"THE SEXUAL FREEDOM OF TODAY FOR MOST PEOPLE IS REALLY ONLY A CONVENTION, AN OBLIGATION, A SOCIAL DUTY, A SOCIAL ANXIETY, A NECESSARY FEATURE OF THE CONSUMER'S WAY OF LIFE." Pier Paolo Pasolini

"IF YOU ARE GOING TO MAKE A FILM ABOUT SEXUAL REVOLUTION, IT’S BEST TO PUT YOUR MARXISM WHERE YOUR MOUTH IS AND MAKE THE MOVIE SEXUALLY EXPLICIT, OR EVEN BETTER, PORNOGRAPHIC, PRIORITISING PRAXIS OVER THEORY." Bruce LaBruce

Essay

A New Sexual Vision for the UK: Bruce LaBruce’s The Visitor

By Simon McCallum

On 20 April 1968 Britain’s shadow defence secretary Enoch Powell addressed a gathering of theConservative Association in the city of Birmingham, in England’s West Midlands. Incendiary enough for him to be sacked by Conservative Party leader Edward Heath the next day, Powell’s notorious “Rivers of Blood” speech deployed a barrage of anti-immigrant rhetoric in the service of an emerging populism which would reshape the political landscape in the UK and beyond into the 21st century.

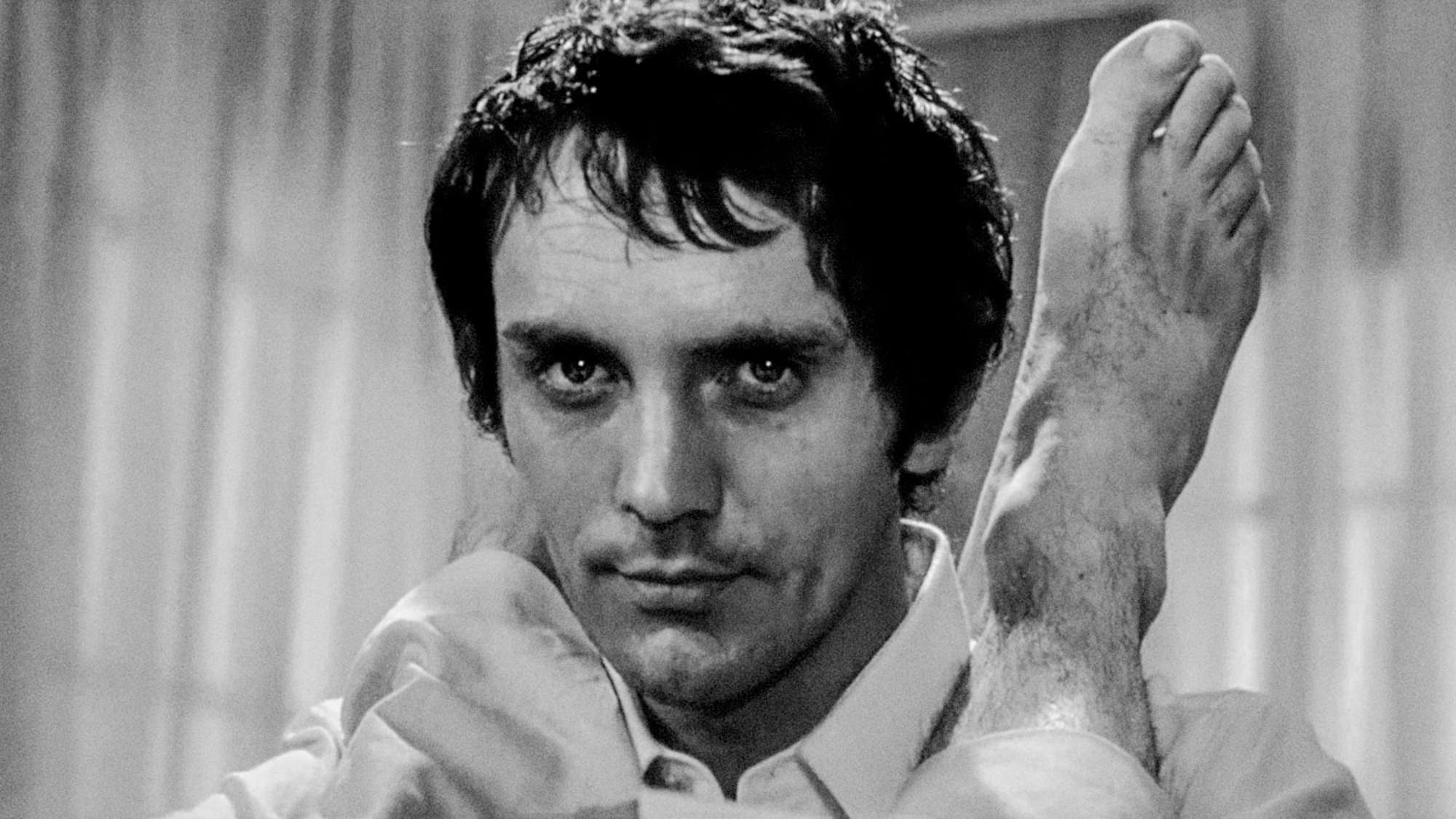

1968 also saw the release of queer Marxist polymath Pier Paolo Pasolini’s feature film Teorema (1968), a dreamlike fable about a mysterious guest wreaking a liberating spiritual and psychosexual havoc upon each member of a wealthy, repressed Milanese family. In Bruce LaBruce’s new feature film and artwork, this visitor is reimagined as a phalanx of identical alien presences emerging from battered suitcases acrossmodern-day London. LaBruce’s film finds Britain in a parlous state: gripped by poisonous inequality, corruption, and consumerism; obsessed with a vanished Empire.

Ruled by a political class and a media in hock to right-wing ideologues, this nation has seen a resurgence of vicious anti-LGBTQ rhetoric, dragging the queer community back to the dark days of Margaret Thatcher. Where Thatcher’s despicable Section 28 legislation and the tabloid media’s scaremongering coverage of the early HIV/AIDS crisis whipped up hatred against gay men, now trans women find themselves scapegoats-in-chief.

The unfolding economic and existential fallout from Britain’s 2016 vote to leave the European Union, following a campaign fuelled by untruths and unchecked xenophobia, lays bare the consequences of Enoch Powell’s rhetoric. Descendants of the ‘Windrush generation’ of Caribbean migrants, integral to Britain’s post-war reconstruction yet treated as second-class citizens, have been forcibly returned to“homelands” they had never known. “Stop the Boats” became the most recent clarion call; the last gasp of a dying regime.

In The Visitor (2023), one new arrival washes up in the polluted shallows of the River Thames, while a radio blares out the kind of dog-whistle propaganda making a comeback in many western democracies (if it ever went away). “I see the River Thames foaming with much blood” spouts this imagined speechmaker, paraphrasing Powell – who himself paraphrased Roman poet Virgil in his 1968 reference to the Tiber. Also in the mix are former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s references to Black citizens ofCommonwealth countries as “flag-waving picaninnies” with “watermelon smiles;” and a nod to the outgoing Conservative government’s proposed solution to the escalating tragedy of desperate migrants being trafficked across the English Channel in small boats: to send them, at enormous cost, to Rwanda.

This is a nation whose privatised water companies have siphoned off so much cash to shareholders that the network is crumbling – to the extent that raw sewage is now being pumped at unprecedented levels into rivers and coastal areas across the UK, polluting them in some cases irrevocably. Even that most British of traditions, the Oxford-Cambridge Boat Race, was not immune to this shitshow, with severalunfortunate rowers stricken with vomiting and diarrhoea as a result.

Rivers of Blood, Rivers of Shit. Welcome to the Hostile Environment.

“When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life,” goes Samuel Johnson’s much-repeated 18th century adage; “for there is in London all that life can afford”. Three centuries later, London remains a microcosm of the world – for better and worse – pulling an international crowd of rich and poor into its hectic orbit.The city’s impact on popular culture is indelible. (Pasolini of course chose Terence Stamp, an icon of the ‘Swinging London’ scene of the 1960s, to play his preternaturally beautiful visitor in Teorema.) But today’s Londoners are tired in a multitude of respects, hustling to keep a roof over their heads in an increasingly untenable housing market blighted by the scourge of parasitic landlordism. At the extreme end of the real estate obscenity spectrum, someone in London earning an average salary would have to work for four thousand years to buy the city’s most expensive apartment. Given the challenges faced by those in regular employment to achieve a decent standard of living in the face of rampant late-stage capitalism, what hope for those who wash up on our shores with nothing?

Meanwhile, on our screens, British film and TV’s disproportionate representation of upper-crust lifeshows little sign of abating, with audiences trapped in the Brideshead Revisited–Downton Abbey–Bridgerton continuum; a perpetual upstairs/downstairs scenario. Among the most talked–about films of 2023 was a country-house potboiler purporting to satirise the British class system, written and directed by a lavishly privileged and well-connected alumna of Marlborough College and Oxford University. Saltburn (2023) harvested cuckoo-in-the-nest tropes from an array of esteemed literary and cinematic sources ranging from The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999) to Teorema, its cavalcade of meme-generating grotesqueries and toffs–in–peril plotline exposing a subliminal horror of the social-climbing “lower orders.”

This may all be painting a rather bleak picture of life in 21st century Britain, one complicated by the apathy that sets in when things begin to feel broken beyond repair – not least for the disenfranchised youth, pitted against a government pondering a reintroduction of military service and older, richer Boomers who (supposedly) hate them, and actually vote. But with The Visitor, LaBruce has no time fordefeatism, channeling the subversive power of sex to effect change from the inside out, and advocating a complete reprogramming of society – starting with the selfish and idle rich.

LaBruce has a long history of championing sexual liberation in his filmmaking, making space for transgressive expressions of gender identity, sexuality, and fetish play. The punk hairdresser enraptured by a neo-Nazi skinhead in No Skin Off My Ass (1991); the amputee sex in his riff on Sunset Boulevard, Hustler White (1996, co-dir. Rick Castro); his “gay Harold and Maude” Gerontophilia (2013); the“twincest” of Saint-Narcisse (2020). In LaBruce’s world, radical politics – in all their chaotic, compromised glory – are inextricably linked to sexual expression: see the “Homosexual Intifada” of The Raspberry Reich (2004), whose use of propagandist slogans tie it most closely to The Visitor; and the rowdy lesbian feminist commune in The Misandrists (2017).

The queer zombie as the ultimate transgressor looms large: in Otto; or, Up with Dead People (2008) and L.A. Zombie (2010). Yet even those most blood-soaked of his films invite a more mischievous, less literal interpretation; that his characters are less monsters from the necrophiliac underworld than schizophrenics inviting us into their psychosis. Though the protagonist of The Visitor is also tearing at the fabric of ordinary life, his antics may not represent a third act in this “zombie cycle.” LaBruce’s “pansexual revolutionary” is here with a clear-eyed mission to deconstruct our minds, not devour our organs.

Speaking of organs: pornography has been a recurring tool in LaBruce’s manifesto since co-founding the Toronto queercore zine J.D.s in 1985, often referencing the porn industry and subverting its tropes in his subsequent filmmaking career. While he has on occasion worked in a more whimsical and romantic register, The Visitor propels us back into hardcore territory. Maid, Mother, Daughter, Father, and Son are put through their sexual paces by their rapacious guest, who invades and injects every orifice with “the virus of homosexual vigour and youth”: colonising the coloniser.

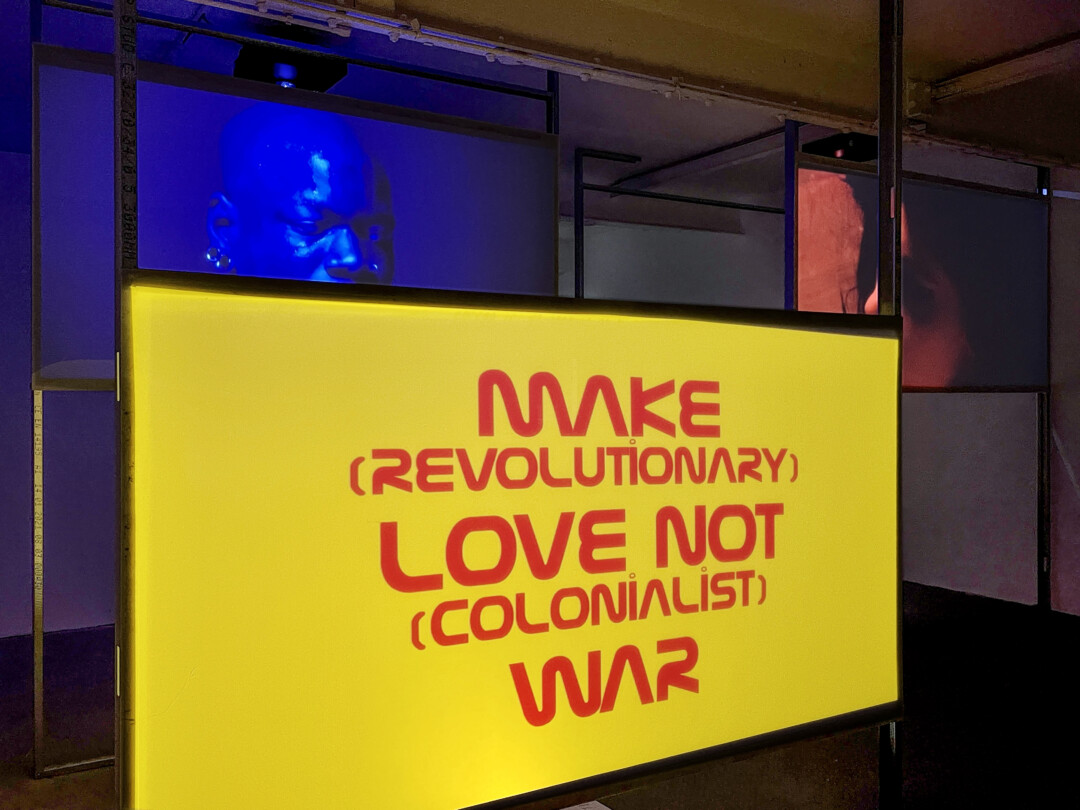

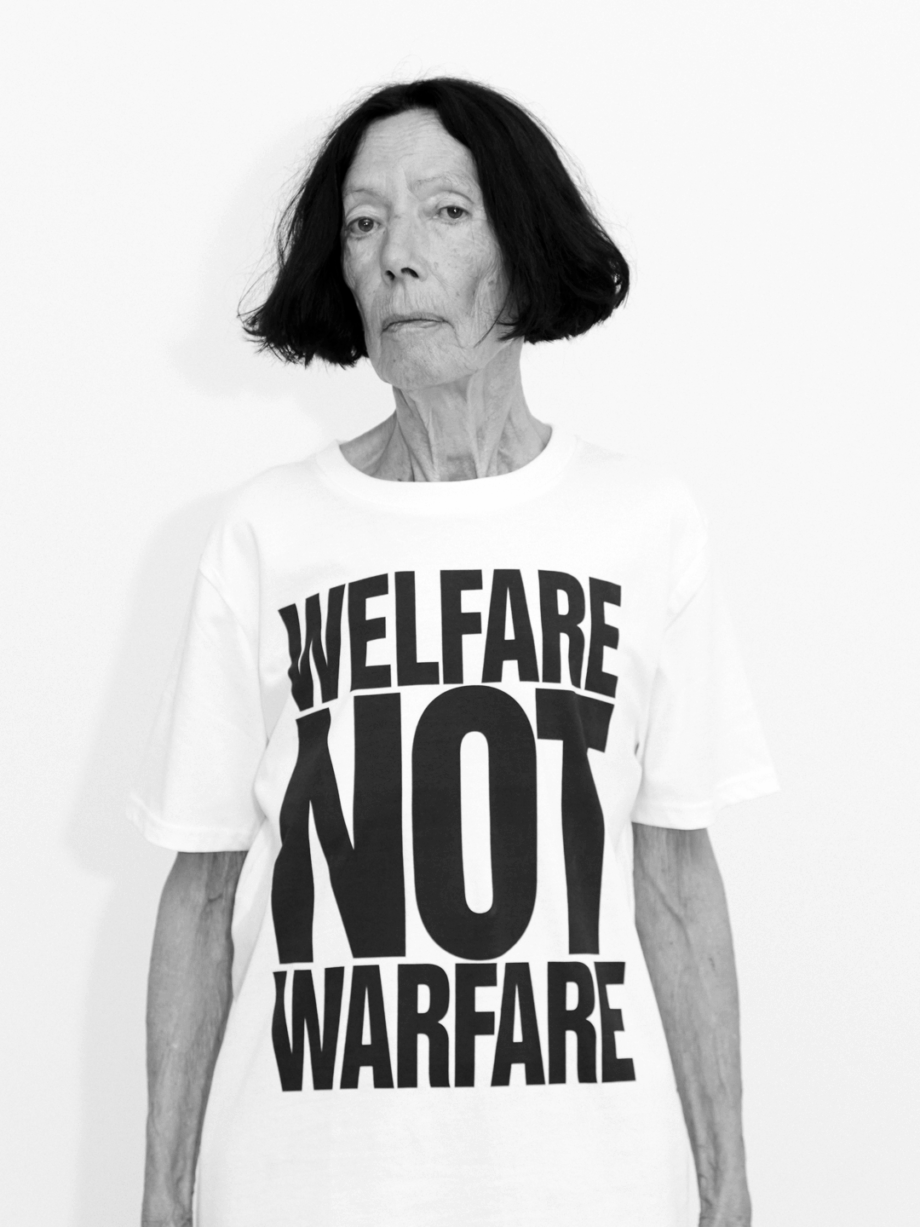

These immersive tableaux of cis, trans, and non-binary bodies coming together in glutinous union are studded with proselytising slogans urging us to MAKE (REVOLUTIONARY) LOVE NOT (COLONIAL) WAR and GIVE PEACE OF ASS A CHANCE! LaBruce also references London’s counter-cultural icons, including doomed gay playwright Joe Orton (PRICK UP YOUR REARS) and punk heroine Poly Styrene (OH BONDAGE, UP YOURS!). The mesmeric mood is soundtracked by DJ and producer Hannah Holland, a mainstay of London’s queer underground circuit.

The family’s echoing architect-designed mansion evokes the anonymous glass boxes favoured by the global oligarchy, whose suspect tax affairs make London a particular hotspot. Designer clothing-addicted Mother epitomises the conspicuous consumption of the new rich (and gets fucked in a giant shopping bag). Pasolini deployed shit-eating as form of sadism in his posthumously released masterpiece Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975) – intending it as a denunciation of mass-produced food – but at dinnertime chez LaBruce, the Visitor’s faecal offerings are served up with a more regenerative purpose.

LaBruce likes to poke at the ties that bind religion and kink. The Maid’s sexual repression, driven by their devout Catholicism, is exploded by the Visitor’s orifice-agnostic attentions (ANAL LIBERATION NOW!). BDSM offers freedom through self-flagellation and auto-erotic asphyxiation but is this so different to the fetishism of religious devotion? The Visitor culminates in the family swapping the city for a Brexit-busting summer sojourn to France; and for the Maid, a renewal of faith on a pilgrimage to Lourdes. One fetish intensifies another.

We leave the family members lost in the mania of their newfound sexual and spiritual liberation. Not everything may be magically well in their world, but something has shifted. LaBruce is still creating change, one fuck at a time. And there is hope that in the UK, the tide is turning, and the scales may soon fall from our eyes.

Simon McCallum is a London-based moving image curator, writer and producer specialising in queer history and representation.

TRAILER

INSTALLATION

In association with

Suggested

ORDER

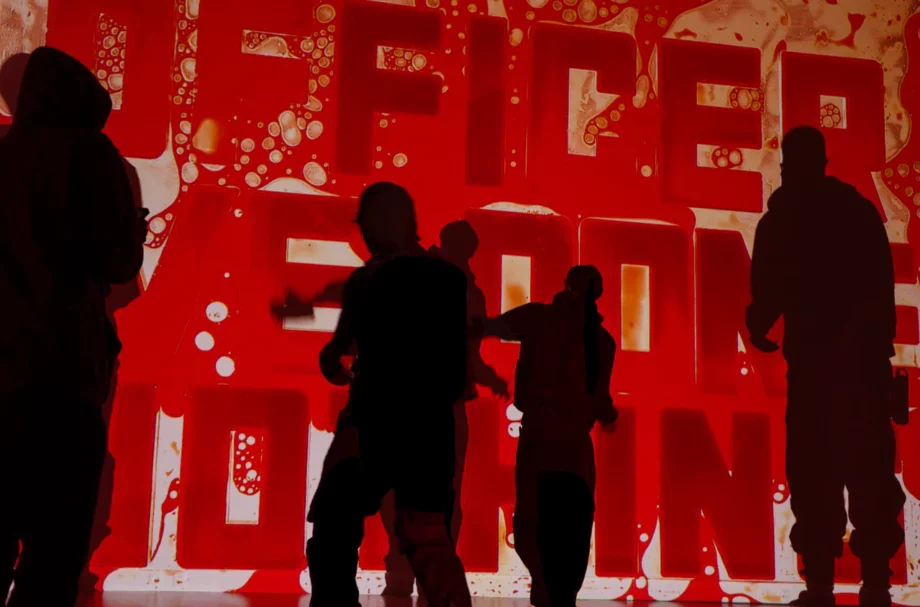

Democracia

Political Drills

Andrei Molodkin, Skengdo x AM and Drillminister

TORTURE

Andres Serrano

END GENOCIDE

Katharine Hamnett

KHAM: THE ROAD

PETR DAVYDTCHENKO

TESTOSTERONE

COUCOU BEBE 75018